Phyllis Ann Boutwell and Eric Gordon Dearborn

Person Page 431

Pedigree

Agnes of Savoy1

F, #10751, b. estimated 1135

Family: Wilhelm I & (b. 1130, d. 25 July 1195)

| Son | Humbert (b. 1172, d. 10 May 1225) |

Events

- 1135BirthEstimated 1135

- 1150~15Marriage | Wilhelm I &1150Age: ~20Birth: 1130 | Geneva, SwitzerlandDeath: 25 July 1195 | Chateau de Novel, Annecy, FranceCitation: 1

| Last Edited | 21 February 2022 05:40:31 |

Citations

- [S979] Our Royal, Titled, Noble and Commoner Ancestors

Pedigree

Beatrice de Vaupergue1

F, #10752, b. estimated 1135

Events

- 1135BirthEstimated 1135

| Last Edited | 21 February 2022 05:52:20 |

Citations

- [S68] Wikipedia

Pedigree

Lucia of Rugen

F, #10753, b. estimated 1193

Parents

Events

- TitleFROM 1202 TO 1206Lucia of Rugen held the title High Duchess Consort of Poland.

- 1186

- 1193BirthEstimated 1193

- TitleFrom 1227 to 1229She held the title High Duchess Consort of Poland.

| Last Edited | 1 March 2025 05:38:32 |

Pedigree

Amytis

F, #10754, b. 470 BCE

Parents

| Father | Xerxes I ("the Great") (b. 518 BCE, d. 465 BCE) |

| Mother | Amestris (b. 505 BCE, d. 425 BCE) |

Events

- 470 BCEBirth470 BCE

| Last Edited | 27 October 2011 06:24:58 |

Pedigree

Darius

M, #10755, b. 465 BCE

Parents

| Father | Xerxes I ("the Great") (b. 518 BCE, d. 465 BCE) |

| Mother | Amestris (b. 505 BCE, d. 425 BCE) |

Events

- NoteFirst born, murdered by his brother Artaxerxes I.

- 465 BCEBirth465 BCE

| Last Edited | 27 October 2011 06:25:22 |

Pedigree

Hystaspes

M, #10756, b. 460 BCE

Parents

| Father | Xerxes I ("the Great") (b. 518 BCE, d. 465 BCE) |

| Mother | Amestris (b. 505 BCE, d. 425 BCE) |

Events

- NoteMurdered by his brother, Artaxerxes I.

- 460 BCEBirth460 BCE

| Last Edited | 27 October 2011 06:25:32 |

Pedigree

Rhodogune

F, #10758, b. 455 BCE

Parents

| Father | Xerxes I ("the Great") (b. 518 BCE, d. 465 BCE) |

| Mother | Amestris (b. 505 BCE, d. 425 BCE) |

Events

- 455 BCEBirth455 BCE

| Last Edited | 27 October 2011 06:25:43 |

Pedigree

Harald III ++ ("Haardrade")1

M, #10759, b. 1015, d. 25 September 1066

Parents

| Father | Sigurd & Styr (b. estimated 960) |

| Mother | Asta & Gudbrandsdatter (b. 970) |

Family: Elisiv ++ of Kiev (b. 1025, d. 1067)

| Daughter | Maria Haraldsdotter (b. 1046, d. 1080) |

| Daughter | Ingegerd of Sweden (b. 1046, d. 1120) |

| Son | Olaf III ++ ("the Quiet; the Peaceful")+ (b. estimated 1050, d. 22 September 1093) |

Events

- BurialTrondheim, Sor Trondelag, NorwayHarald III ++ ("Haardrade") was buried in Trondheim, Sor Trondelag, Norway, Mary Church; moved to Helgeseter Priory.Citation: 2

- 1015

- 1043~28

- 1066~51

| Last Edited | 2 May 2023 06:12:21 |

Citations

Pedigree

Peroz II

M, #10760, b. estimated 634

Parents

| Father | Yazdagard III (b. 615, d. 651) |

| Mother | Manyanh (b. 622) |

Events

- 634BirthEstimated 634

| Last Edited | 29 October 2011 10:00:27 |

Pedigree

Thomas Additon, Jefferson

M, #10762, b. 1832, d. 1897

Parents

| Father | Thomas Additon (b. 1794, d. 1869) |

Family: Rosilla S (b. estimated 1837)

| Son | Elwin Everett Additon+ (b. 1864, d. 1942) |

| Daughter | Annie Additon, S (b. estimated 1866) |

Events

- OccupationThomas Additon, Jefferson, was a farmer.

- 1832Birth1832

- 1897~65Death1897 | Leeds, Androscoggin, ME, US

| Last Edited | 1 January 2012 08:12:52 |

Pedigree

Thomas Additon

M, #10763, b. 1794, d. 1869

Family:

| Son | Thomas Additon, Jefferson+ (b. 1832, d. 1897) |

Events

- 1794Birth1794

- 1869~75Death1869

| Last Edited | 22 July 2011 22:13:54 |

Pedigree

Rosilla S

F, #10764, b. estimated 1837

Family: Thomas Additon, Jefferson, (b. 1832, d. 1897)

| Son | Elwin Everett Additon+ (b. 1864, d. 1942) |

| Daughter | Annie Additon, S (b. estimated 1866) |

Events

- 1837BirthEstimated 1837

| Last Edited | 29 October 2011 19:46:26 |

Pedigree

Annie Additon, S

F, #10765, b. estimated 1866

Parents

| Father | Thomas Additon, Jefferson (b. 1832, d. 1897) |

| Mother | Rosilla S (b. estimated 1837) |

Events

- 1866BirthEstimated 1866

| Last Edited | 29 October 2011 19:46:30 |

Pedigree

Orland Additon

M, #10766, b. estimated 1897, d. 1931

Parents

| Father | Elwin Everett Additon (b. 1864, d. 1942) |

| Mother | Mary (b. estimated 1869) |

Events

- OccupationOrland Additon was a farmer.

- 1897BirthEstimated 1897

- 1931~34Death1931

| Last Edited | 29 October 2011 11:00:05 |

Pedigree

Mary

F, #10767, b. estimated 1869

Family: Elwin Everett Additon (b. 1864, d. 1942)

| Son | Orland Additon (b. estimated 1897, d. 1931) |

| Daughter | Vina Annie Additon+ (b. 14 August 1899) |

Events

- 1869BirthEstimated 1869

| Last Edited | 29 October 2011 11:00:00 |

Pedigree

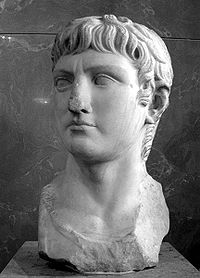

Germanicus Aggrippina the Elder (Major)

M, #10769, b. 24 May 015 BCE, d. 10 October 019

Parents

| Father | Nero Claudius & Drusas (b. about 14 January 038 BCE, d. 14 September 009) |

| Mother | Antonia & ("the Younger") (b. about 040 BCE, d. 1 May 037) |

Family: Aggrippina ("The Elder") (b. 014 BCE, d. 18 October 033)

| Son | Nero Germanicus, Julius Caesar (b. 006, d. 030) |

| Son | Drusus Caesar (b. 007, d. 033) |

| Son | Caligula (b. 31 August 012, d. 24 January 041) |

| Daughter | Aggripina ("The Younger")+ (b. 7 November 015, d. 23 March 059) |

| Daughter | Julia Drusilla (b. 16 September 016, d. 10 June 038) |

| Daughter | Julia Livilla (b. 018, d. 041) |

Germanicus

Events

- NoteGermanicus Julius Caesar (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19), commonly known as Germanicus, was a member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and a prominent general of the early Roman Empire. He was born in Rome, Italia, and was named either Nero Claudius Drusus after his father or Tiberius Claudius Nero after his uncle. He received the agnomen Germanicus in 9 BC, when it was posthumously awarded to his father in honour of his victories in Germania.

Germanicus was the grandson-in-law and great-nephew of the Emperor Augustus, nephew and adoptive son of the Emperor Tiberius, father of the Emperor Caligula, brother of the Emperor Claudius, and the maternal grandfather of the Emperor Nero.

Germanicus was born in Rome in 15 BC. His parents were the general Nero Claudius Drusus (son of Empress Livia Drusilla, third wife of Emperor Augustus) and Antonia Minor (the younger daughter of the triumvir Mark Antony and Octavia Minor, sister of Augustus). Livilla was his sister and the future Emperor Claudius was his younger brother.

Germanicus married his maternal second cousin Agrippina the Elder, a granddaughter of Augustus, between 5 and 1 BC. The couple had nine children. Two died very young; another, Gaius Julius Caesar, died in early childhood. The remaining six were: Nero Caesar, Drusus Caesar, the Emperor Caligula, the Empress Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla. Through Agrippina the Younger, Germanicus was the Emperor Nero's maternal grandfather.

Germanicus became immensely popular among the citizens of Rome, who enthusiastically celebrated his military victories. He was also a favourite with Augustus, his great-uncle, who for some time considered him heir to the Empire. In AD 4, persuaded by Livia, his wife, Augustus decided in favour of Tiberius, his stepson from Livia's first marriage to Tiberius Nero. However, Augustus compelled Tiberius to adopt Germanicus as a son and to name him as his heir (see Tacitus, Annals IV.57). Upon this adoption, Germanicus's name was changed to Germanicus Julius Caesar. He also became the adoptive brother of Tiberius's natural son Drusus the Younger.

Germanicus held several military commands, leading the army in the campaigns in Pannonia and Dalmatia. He is recorded to have been an excellent soldier and an inspired leader, loved by the legions. In the year 12 he was appointed consul after five mandates as quaestor.

[edit] Commander of Germania

The death of Germanicus, by Nicholas Poussin, laments the passing of Rome's last Republican.After the death of Augustus in 14, the Senate appointed Germanicus commander of the forces in Germania. A short time after, the legions rioted on the news that their recruitments would not be marked back down to 16 years from the now standard 20. Refusing to accept this, the rebel soldiers cried for Germanicus as emperor. Germanicus put down this rebellion himself, to honour Augustus' choice and stamp out the mutiny, preferring to continue only as a general. In a bid to secure the loyalty of his troops and his own popularity with them and with the Roman people, he led them on a spectacular but brutal raid against the Marsi, a German tribe on the upper Ruhr river, in which he massacred much of the tribe.

During each of the next two years, he led his 8-legion army into Germany against the coalition of tribes led by Arminius, which had successfully overthrown Roman rule in a rebellion in 9. His major success was the capture of Arminius' wife Thusnelda in May 15. He let Arminius' wife sleep in his quarters during the whole of the time she was a prisoner. He said, "They are women and they must be respected, for they will be citizens of Rome soon"[citation needed]. He was able to devastate large areas and eliminate any form of active resistance, but the majority of the Germans fled at the sight of the Roman army into remote forests. The raids were considered a success since the major goal of destroying any rebel alliance networks was completed.

After visiting the site of the disastrous Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, where 20,000 Romans had been killed in 9 CE, and burying their remains, he launched a massive assault on the heartland of Arminius' tribe, the Cheruscans. Arminius initially lured Germanicus' cavalry into a trap and inflicted minor casualties, until successful fighting by the Roman infantry caused the Germans to break and flee into the forest. This victory, combined with the fact that winter was fast approaching, meant Germanicus's next step was to lead his army back to its winter quarters on the Rhine.

In spite of doubts on the part of his uncle, Emperor Tiberius, Germanicus managed to raise another huge army and invaded Germany again the next year, in 16. He forced a crossing of the Weser near modern Minden, suffering heavy losses, and then met Arminius' army at Idistaviso, further up the Weser, near modern Rinteln, in an engagement often called the Battle of the Weser River. Germanicus's leadership and command qualities were shown in full at the battle as his superior tactics and better trained and equipped legions inflicted huge casualties on the German army with only minor losses. One final battle was fought at the Angivarian Wall west of modern Hanover, repeating the pattern of high German fatalities forcing them to flee. With his main objectives reached and with winter approaching Germanicus ordered his army back to their winter camps, with the fleet occasioning some damage by a storm in the North Sea. Although only a small number of soldiers died it was still a bad ending for a brilliantly fought campaign. After a few more raids across the Rhine, which resulted in the recovery of two of the three legion's eagles lost in 9, Germanicus was recalled to Rome and informed by Tiberius that he would be given a triumph and reassigned to a different command.

Despite the successes enjoyed by his troops, Germanicus' German campaign was in reaction to the mutinous intentions of his troops, and lacked any strategic value. In addition he engaged the very German leader (Arminius) who had destroyed three Roman legions in 9, and exposed his troops to the remains of those dead Romans. Furthermore, in leading his troops across the Rhine, without recourse to Tiberius, he contradicted the advice of Augustus to keep that river as the boundary of the empire, and opened himself to doubts about his motives in such independent action. These errors in strategic and political judgement gave Tiberius reason enough to recall his nephew.[1]

[edit] Command in Asia and death

Benjamin West, Agrippina landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, Oil on canvas, c. 1768.Germanicus was then sent to Asia, where in 18 he defeated the kingdoms of Cappadocia and Commagene, turning them into Roman provinces. During a sightseeing trip to Egypt (not a regular province, but the personal property of the Emperor) he seems to have unwittingly usurped several imperial prerogatives.[2] The following year he found that the governor of Syria, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, had canceled the provincial arrangements that he had made. Germanicus in turn ordered Piso's recall to Rome, although this action was probably beyond his authority.[2] In the midst of this feud Germanicus died suddenly in Antioch. His death aroused much speculation, with several sources blaming Piso, under orders from Emperor Tiberius. This was never proven, and Piso later died while facing trial (ostensibly by suicide, but Tacitus supposes Tiberius may have had him murdered before he could implicate the emperor in Germanicus' death). He feared the people of Rome knew of the conspiracy against Germanicus, but Tiberius' jealousy and fear of his nephew's popularity and increasing power was the true motive.[citation needed]

The death of Germanicus in what can only be described as dubious circumstances greatly affected Tiberius' popularity in Rome, leading to the creation of a climate of fear in Rome itself. Also suspected of connivance in his death was Tiberius' chief advisor, Sejanus, who would, in the 20s, create an atmosphere of fear in Roman noble and administrative circles by the use of treason trials and the role of "informers."[citation needed]

[edit] Posthumous honorsGermanicus’ death brought much public grief in Rome and throughout the Roman Empire. His death was announced in Rome during December of 19. There was public mourning during the festive days in December. The historians Tacitus and Suetonius record the funeral and posthumous honors of Germanicus. At his funeral, there were no procession statues of Germanicus. There were abundant eulogies and reminders of his fine character.

His posthumous honors included his name was placed into the following: the Carmen Saliare; the Curule chairs; placed as an honorary seat of the Brotherhood of Augustus and his coffin was crowned by oak-wreaths. Other honors include his ivory statue as head of procession of the Circus Games; his posts of priest of Augustus and Augur were to be filled by members of the imperial family; knights of Rome gave his name to a block of seats to a theatre in Rome.

Arches were raised to him throughout the Roman Empire in particularly, arches that recorded his deeds and death at Rome, Rhine River and Nur Mountains. In Antioch, where he was cremated had a sepulchre and funeral monument dedicated to him.

On the day of Germanicus’ death his sister Livilla gave birth to twins. The second, named Germanicus, died young. In 37, when Germanicus’ only remaining son, Caligula, became emperor, he renamed September Germanicus in honor of his father. Many Romans considered him as their equivalent to King Alexander the Great. Germanicus' grandson was Emperor Nero Caesar-died 68 AD-the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. - 015 BCEBirth24 May 015 BCE

- 01934Death10 October 019

| Last Edited | 22 July 2011 22:13:54 |

Pedigree

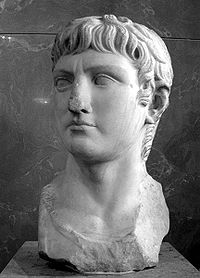

Aggrippina ("The Elder")

F, #10770, b. 014 BCE, d. 18 October 033

Parents

| Father | Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (b. about 063 BCE, d. 012 BCE) |

| Mother | Julia the Elder (b. 30 October 039 BCE, d. 014) |

Family: Germanicus Aggrippina the Elder (Major) (b. 24 May 015 BCE, d. 10 October 019)

| Son | Nero Germanicus, Julius Caesar (b. 006, d. 030) |

| Son | Drusus Caesar (b. 007, d. 033) |

| Son | Caligula (b. 31 August 012, d. 24 January 041) |

| Daughter | Aggripina ("The Younger")+ (b. 7 November 015, d. 23 March 059) |

| Daughter | Julia Drusilla (b. 16 September 016, d. 10 June 038) |

| Daughter | Julia Livilla (b. 018, d. 041) |

Events

- NoteVipsania Agrippina or most commonly known as Agrippina Major or Agrippina the Elder (Major Latin for the elder, Classical Latin: AGRIPPINA•GERMANICI,[1] 14 BC – 18 October 33) was a distinguished and prominent granddaughter of the Emperor Augustus. Agrippina was the wife of the general, statesman Germanicus and a relative to the first Roman Emperors. She was the second granddaughter of the Emperor Augustus, sister-in-law, stepdaughter and daughter-in-law of the Emperor Tiberius, mother of the Emperor Caligula, maternal second cousin and sister-in-law of the Emperor Claudius and the maternal grandmother of the Emperor Nero.

Agrippina was born as the second daughter and fourth child to Roman Statesman and Augustus’ trusted ally Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder. Agrippina’s mother Julia was the only natural child born to Augustus from his second marriage to noblewoman Scribonia.

Her father’s marriage to Julia was his third marriage. From Agrippa’s previous two marriages, Agrippina had two half-sisters: Vipsania Agrippina and Vipsania Marcella Agrippina. Vipsania Agrippina was Agrippa’s first daughter and first child from his first marriage to Pomponia Caecilia Attica. She became Tiberius's first wife and was the mother of his natural son Drusus Julius Caesar. Vipsania Agrippina later married senator and consul Gaius Asinius Gallus Saloninus after Tiberius was forced to divorce her and marry Julia the Elder. Vipsania Marcella was Agrippa’s second child from his second marriage to Augustus’ first niece and the paternal cousin of Julia the Elder, Claudia Marcella Major. Vipsania Marcella was the first wife of the general Publius Quinctilius Varus.

Her mother’s marriage to Agrippa was her second marriage, as Julia the Elder was widowed from her first marriage, to her paternal cousin Marcus Claudius Marcellus and they had no children. From the marriage of Julia and Agrippa, Agrippina had four full-blood siblings: a sister Julia the Younger and three brothers: Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar and Agrippa Postumus. Agrippina was born in Athens, as in the year of her birth Agrippa was in that city completing official duties on behalf of Augustus. Her mother and her siblings had travelled with Agrippa. Later Agrippina’s family returned to Rome.

In 12 BC, Agrippina’s father died. Augustus had forced his first stepson Tiberius to end his happy first marriage to Vipsania Agrippina to marry Julia the Elder. The marriage of Julia and Tiberius was not a happy one. In 2 BC Augustus exiled Agrippina’s mother on the grounds that she had committed adultery, thereby causing a major scandal. Julia was banished for her remaining years and Agrippina never saw her again. Around this time, to avoid any scandals Tiberius divorced Julia and left Rome to live on the Greek island of Rhodes.

With her siblings, Agrippina was raised in Rome by her maternal grandfather and maternal step-grandmother Livia Drusilla. Livia was the first Roman Empress and was Augustus’ third wife (from Livia’s first marriage to praetor Tiberius Nero, she had two sons: the emperor Tiberius and the general Nero Claudius Drusus. Augustus was Livia's second husband).

According to Suetonius, Agrippina had a strict upbringing and education. Her education included how to spin and weave and she was forbidden to say or do anything, either in public or private. Augustus made her record any daily activities she did in the imperial day book and the emperor took severe measures in preventing Agrippina from forming friendships, without his consent. As a member of the imperial family, Agrippina was expected to have and show strict traditional Roman virtues for a woman that was frugality, chastity and domesticity. Agrippina and Augustus had a close relationship.

[edit] The wife of GermanicusBetween 1 BC-5, Agrippina married her second maternal cousin Germanicus. Germanicus was the first son born to Antonia Minor and Nero Claudius Drusus. Antonia Minor was the second daughter born to Octavia Minor and triumvir Mark Antony, hence Antonia’s maternal uncle was Augustus. Germanicus was a popular general and politician. Augustus ordered Tiberius to adopt Germanicus as his son and heir. Germanicus was always favored by his great uncle and hoped that he would succeed Tiberius, who had been adopted by Augustus as his heir and successor. Agrippina and Germanicus were devoted to each other. She was a loyal, affectionate wife, who supported her husband. The Roman historian Tacitus states that Agrippina had an ‘impressive record as wife and mother’.

Agrippina and Germanicus in their union had nine children, whom three died young. The six children who survived to adulthood were the sons: Nero Caesar, Drusus Caesar and Caligula born as Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus and the daughters Julia Agrippina or Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla and Julia Livilla. Caligula would become future Roman Emperor. Agrippina the Younger would become a future Roman Empress and mother to the later Emperor Nero. Their children were born at various places throughout the Roman Empire and Agrippina acquired a well-deserved reputation for successful childbearing. Eventually Agrippina was proud of her large family and this was apart of the reason, she was popular with Roman citizens.

According to Suetonius who had cited from Pliny the Elder, Agrippina had borne to Germanicus, a son called Gaius Julius Caesar who had a lovable character. This son died young. The child was born at Treveri, near the village of Ambitarvium, just before the junction of the Moselle River and the Rhine River (modern Koblenz Germany). At this spot, there were local altars inscribed as a dedication to Agrippina: “IN HONOR OF AGRIPPINA’S PUERPERIUM”, puerperium means child-bearing for a boy.

Germanicus was a candidate for future succession and had won fame campaigning in Germania and Gaul. During the military campaigns, Agrippina accompanied Germanicus with their children. Agrippina’s actions were considered unusual as for a Roman wife, because a conventional Roman wife was required to stay home. Agrippina had earned herself a reputation as a heroic woman and wife. During her time in Germania, Agrippina had proved herself to be an efficient and effective diplomat. Agrippina had reminded Germanicus on occasion of his relation to Augustus.

A few months before Augustus’ death in 14, the emperor wrote and sent a letter to Agrippina mentioning how Caligula must be future emperor because at that time, no other child had this name.

The letter reads:

Yesterday I made arrangements for Talarius and Asillius to bring your son Gaius to you on the eighteenth of May, if the gods will. I am also sending with him one of my slaves, a doctor who as I have told Germanicus in a letter, need not be returned to me if he proves of use of you. Goodbye my dear Agrippina! Keep well on the way to your Germanicus!

Agrippina landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus, Oil on canvas, c. 1768.Agrippina and Germanicus travelled to the Middle East in 19, incurring the displeasure of Tiberius. Germanicus quarrelled with Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, the governor of Syria and died in Antioch in mysterious circumstances. It was widely suspected that Germanicus had been poisoned or perhaps on the orders of Tiberius. Agrippina was in grief when Germanicus died. She returned with her children to Italy with Germanicus’ ashes. The Roman citizens had great sympathy for Agrippina and her family. She returned to Rome to avenge his death and boldly accused Piso of the murder of Germanicus. According to Tacitus (Annals 3.14.1), the prosecution could not prove the poisoning charge, but other charges of treason seemed likely to stick and Piso committed suicide.

[edit] Time in Rome, downfall and posthumous honorsFrom 19 to 29, Agrippina lived on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Her remaining children were raised between her, Livia Drusilla and Germanicus’ mother Antonia Minor. Agrippina had become lonely, distressed, physically ill and many of her relatives had died. Agrippina had a hasty, uncomfortable relationship with Tiberius and possibly with Tiberius’ mother Livia. She became involved in politics in Tiberius’ imperial court, became an advocate for her sons to succeed Tiberius, and opposed Tiberius’ natural son and natural grandson Tiberius Gemellus for succession.

She was unwise in her complaints about Germanicus’ death to Tiberius. Tiberius took Agrippina by her hand and quoted the Greek line: “And if you are not queen, my dear, have I then you wrong?”

Agrippina became involved in a group of Roman Senators who opposed the growing power and influence of the notorious Praetorian Guard Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius began to distrust Agrippina. In 26, Agrippina requested Tiberius to allow her to marry her brother-in-law, Roman Senator Gaius Asinius Gallus Saloninus. However, Tiberius didn’t allow her to marry Saloninus, because of political implications the marriage could have.

Tiberius carefully staged to invite Agrippina to dinner at the imperial palace. At dinner, Tiberius offered Agrippina an apple as a test of Agrippina’s feelings for the emperor. Agrippina had suspected that the apple could carry a certain death and refused to taste the apple. This was the last time that Tiberius invited Agrippina to his dinner table. Agrippina later stated that Tiberius tried to poison her.

In 29, Agrippina and her sons Nero and Drusus, were arrested on the orders of Tiberius. Tiberius falsely accused Agrippina of planning to take sanctuary besides the image of Augustus or with the Roman Army abroad. Agrippina and her sons were put on trial by the Roman Senate. She was banished on Tiberius’ orders to the island of Pandataria (now called Ventotene) in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the coast of Campania. This was the island where her mother was banished.

In prison at Pandataria, Agrippina protested violently. On one occasion, Tiberius ordered a centurion to flog her and in the course she lost an eye. Refusing to eat, Agrippina was force-fed but later starved herself to death. There is a possibility malnutrition contributed to her death. She died 18 October 33. Agrippina’s son Drusus died of starvation being imprisoned in Rome and her other son Nero either committed suicide or was murdered after his trial in 29. The notorious guard Sejanus was murdered in 31 on the orders of Tiberius. Tiberius suspected Sejanus of plotting to overthrow the emperor.

After the death of Agrippina, Tiberius wickedly slandered her memory. Tiberius had stated while Agrippina lived, he showed her clemency. Tiberius was able to persuade the Roman Senate to decree Agrippina’s birthday as a day of ill omen.

In March 37, Tiberius died and Agrippina’s remaining son Caligula succeeded as emperor. After Caligula delivered Tiberius’ eulogy, Caligula sailed to Pandataria and the Pontine Islands and returned with the ashes of his mother and brother Nero. Caligula returned with their ashes in urns in his own hands.

Caligula Depositing the Ashes of his Mother and Brother in the Tomb of his Ancestors, by Eustache Le Sueur, 1647As proof of devotion to his family, Caligula arranged the most distinguished soldiers available to carry the urns of his mother and two brothers in two biers at noon in Rome, when the streets were at their busiest, to the Mausoleum of Augustus. A bronze medal on display in the British Museum shows Agrippina’s ashes being brought back to Rome by Caligula.

Cinerary urn of Agrippina, in the tabularium.Caligula appointed an annual day each year in Rome, for people to offer funeral sacrifices to honor their late relatives. As a dedication to Agrippina, Caligula set aside the Circus Games to honor the memory of his late mother. On the day that the Circus Games occurred, Caligula had a statue made of Agrippina’s image to be paraded in a covered carriage at the Games.

After the Circus Games, Caligula ordered written evidence of the court cases from Tiberius’ treason trials to be brought to the Forum to be burnt, first being the cases of Agrippina and her two sons.

[edit] The historiansAccording to Suetonius, Caligula nursed a rumor that Augustus and Julia the Elder had an incestuous union from which Agrippina the Elder had been born. According to Tacitus, Agrippina’s eldest daughter Agrippina the Younger had written memoirs for posterity. One memoir was an account of her mother’s life. A second memoir was about the fortunes of her mother’s family and the last memoir recorded the misfortunes (casus suorum) of the family of Agrippina and Germanicus. Unfortunately these memoirs are now lost.

[edit] PersonalityAgrippina is regarded in ancient and modern historical sources as a Roman Matron with a reputation as a great woman, who had an excellent character and had outstanding Roman morals. She was a dedicated, supporting wife and mother who looked out for the interests of her children and the future of her family.

Tacitus describes Agrippina’s character as “determined and rather excitable”. Throughout her life, Agrippina always proudly and arrogantly prized her ancestry from Augustus. However Agrippina’s constant dwelling of her noble birth and her stating being the "sole surviving offspring of Augustus" (Tacitus, Annals 3.4) may have contributed to her downfall.

Although Agrippina was an innocent victim of Tiberius’ tyranny, Agrippina dwelling on her ancestry, was a complete insult to Tiberius and Livia Drusilla. Tiberius was the adopted son and heir of Augustus, while Livia was adopted into the imperial family after the death of Augustus. Agrippina’s attitude in her ancestry became a challenge to the position of Tiberius as successor of Augustus and ruling as an emperor, which effected future succession in the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

[edit] LegacyAgrippina the Elder is considered the most prominent and distinguished grandchild born to Rome’s first Emperor. She is also considered one of the most prominent women in the Julio-Claudian dynasty; one of the most virtuous and heroic women of antiquity and of the first century.

She was the first Roman woman of the Roman Empire to have travelled with her husband to Roman military campaigns; to support and live with the Roman Legions. Agrippina was the first Roman matron to have more than one child from her family to reign on the Roman throne. Apart from being the late maternal grandmother of Nero, she was the late paternal grandmother of Princess Julia Drusilla, the child of Caligula. Through Nero, Agrippina was the paternal great-grandmother of Claudia Augusta, (Nero's only child through his second marriage to Poppaea Sabina).

Although Agrippina was a great example of a Roman Matron, she set a precedent for many upcoming Roman aristocratic women. She paved the way for women to wield influence and power in Roman politics, particularly in the Imperial Court, Senate and Army. She also set a precedent for wives who were Roman Empresses or female relatives of the ruling Imperial Family of the day to assist in the ruling and decision making policies that could effect, change and shape the Empire. The aristocratic women of the empire had more power and influence, than their predecessors in the Roman Republic. Through the precedents that were set by Agrippina, some aristocratic women later became patrons of learning, culture or charity and advisors to the later Roman Emperors.

From the memoirs written by Agrippina the Younger, Tacitus used the memoirs to extract information regarding the family and fate of Agrippina the Elder, when Tacitus was writing The Annals. There is a surviving portrait of Agrippina the Elder in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. - 014 BCEBirth014 BCE | Athens, Attica, Greece

- 033~47Death18 October 033 | Pandataria

| Last Edited | 2 October 2011 14:17:50 |

Pedigree

Livilla

F, #10772, b. 013 BCE, d. 031

Parents

| Father | Nero Claudius & Drusas (b. about 14 January 038 BCE, d. 14 September 009) |

| Mother | Antonia & ("the Younger") (b. about 040 BCE, d. 1 May 037) |

Events

- Note(Claudia) Livia Julia (Classical Latin: LIVIA•IVLIA[1]) (c. 13 BC – 31 A.D.) was the only daughter of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia Minor. She was named after her grand-mother, Augustus' wife Livia Drusilla, and commonly known by her family nickname Livilla (the "little Livia").

She was twice married to the potential successor in the Julio-Claudian dynasty, first to Augustus' grandson Gaius Caesar (died 4 AD) and later to Tiberius' son Drusus (died 23 AD). Allegedly, she helped her lover Sejanus in poisoning her husband and died shortly after Sejanus fell from power in 31 AD.

Livilla was married twice, first in 2 BC to Gaius Caesar, Augustus' grandson and potential successor. Thus, Augustus had chosen Livilla as the wife of the future Emperor. This splendid royal marriage probably gave Livilla grand aspirations for her future, perhaps at the expense of the ambition of Augustus' granddaughters, Agrippina the Elder and Julia the Younger. However, Gaius died in 4 AD, cutting short Augustus' and Livilla's plans.

In the same year, Livilla married her cousin Drusus Julius Caesar, the son of Tiberius. When Tiberius succeed Augustus as Emperor in 14 AD, Livilla again was the wife of a potential successor. Drusus and Livilla had three children, a daughter names Julia in 5 AD and twin brothers in 19 AD: of these Germanicus Gemellus died in 23, whereas Tiberius Gemellus survived his infancy.

[edit] Livilla's standing in her familyTacitus reports that Livilla was a remarkably beautiful woman, despite the fact she was rather ungainly as a child.[2] The Senatus Consultum de Cn. Pisone patre[3] indicates that she was held with the highest esteem by her uncle and father-in-law, Tiberius, and by her grandmother Livia Drusilla.[4]

According to Tacitus, she felt resentment and jealousy against her sister-in-law Agrippina the Elder, the wife of her brother Germanicus, to whom she was unfavourably compared.[5] Indeed, Agrippina fared much better in producing imperial heirs to the household (being the mother of the Emperor Caligula and Agrippina the Younger) and was much more popular. Suetonius reports that she despised her younger brother Claudius; having heard he would one day become Emperor, she deplored publicly such a fate for the Roman people.[6]

As most of the female members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, she may also have been very ambitious, in particular for her male offspring.[7]

[edit] Affair with SejanusPossibly even before the birth of the twins, Livilla had an affair with Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the praetorian prefect of Tiberius - later on, some (including Tiberius suspected Sejanus to have fathered the twins. Drusus, heir apparent since the death of Germanicus in 23 AD, died in the same year, shortly after striking Sejanus in an argument. According to Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio, Sejanus had poisoned Drusus, not only because he feared the wrath of the future Emperor but also because he had designs on the supreme power, and aimed at removing a potential competitor -, with Livilla as his accomplice. If Drusus was indeed poisoned, his death aroused no suspicions at the time.

Sejanus now wanted to marry the widowed Livilla. Tiberius in 25 rejected such a request but in 31 eventually gave way. In the same year, the Emperor received evidence from Antonia Minor, his sister-in-law, that Sejanus planned to overthrow him. Tiberius had Sejanus denounced in the Senate, then arrested and dragged off to prison to be put to death. A bloody purge then erupted in Rome, most of Sejanus' family (including his children) and followers sharing his fate.

[edit] Accusations and deathHearing of the death of her children, Sejanus' former wife Apicata committed suicide. Before her death, she addressed a letter to Tiberius, accusing Sejanus and Livilla of having poisoned Drusus. Drusus' cupbearer Lygdus and Livilla's physician Eudemus were questioned and under torture confirmed Apicata's accusation.

Livilla died shortly afterwards, either being killed or by suicide. According to Cassius Dio, Tiberius handed Livilla over to her mother, Antonia Minor, who locked her up in a room and starved her to death.[8]

Early in 32, the Senate proposed "terrible decrees...against her very statues and memory".[9]

Posthumously, there were further allegations of adultery with her physician Eudemus[10] and with the senator and poet Mamercus Aemilius Scaurus.[11]

[edit] Portraiture

Woman on the Great Cameo of France, sometimes identified as Livilla.The iconographic identification of Livilla has posed many problems to date, mainly due to the damnatio memoriae voted against her by the Senate after her death. Several possibilities have been advanced but none has to date received widespread acceptance. However, a portrait type that survives in at least three replicas and which we may refer to as the Alesia type may very well represent Livilla.[12] As seen in the picture above, it shows the head of a lady in her blossom years, with a hairstyle clearly from the tiberian period. The physiognomy is close but not identical to portraits of Antonia Minor, Livilla's mother, and some replicas seem to bear the marks of voluntary damage (that one would expect from a damnatio memoriae). For all these reasons, it has been proposed to see in this portrait type a representation of Livilla.

A cameo portrait of a lady with the silhouettes of two infants, has been tentatively identified as Livilla.[13] Although it may be possible that the seated woman on right on the Great Cameo of France represents Livilla, it seems more probable that the female figure seated on the left and holding a roll is in fact representing Livilla, depicted there as the widowed wife of Drusus the Younger, seen just above her as one of the three heavenly imperial male figures.[14]

[edit] Appearance in mediaThe character of Livilla appeared in the 1968 British television series The Caesars and was portrayed by Suzan Farmer. She also appeared in the 1976 BBC TV series adoption of I, Claudius and was played by Patricia Quinn. In the 1985 mini-series A.D. Anno Domini, which chronicles the very beginning of Christianity and its struggle with the Roman Empire, the character of Livilla was played by Susan Sarandon. - 013 BCEBirth013 BCE

- 031~44Death031

| Last Edited | 22 July 2011 22:13:54 |

Pedigree

Uthman ibn Abi-As

M, #10774, b. estimated 693

Parents

| Father | Abu Al-As ibn Umayyah (b. 550) |

| Mother | Ruqayya (b. 555) |

Events

- 693BirthEstimated 693

| Last Edited | 22 July 2011 22:13:54 |

Pedigree

Affan

M, #10775, b. estimated 696

Parents

| Father | Abu Al-As ibn Umayyah (b. 550) |

| Mother | Ruqayya (b. 555) |

Events

- 696BirthEstimated 696

| Last Edited | 22 July 2011 22:13:54 |